literature, community, education, social justice

OTHER NON-FICTION

“Transforming silence into language and action” — Audre Lorde

Braiding Sweetgrass (2013) - Robin Wall Kimmerer

“Ceremony brought the quiescent back to life, opened my mind and heart to what I knew, but had forgotten…Ceremony is a vehicle for belonging—to a family, to a people, and to the land” (pp. 36-37).

“There was a time when I teetered precariously with an awkward foot in each of two worlds—the scientific and the Indigenous. But then I learned to fly. Or at least try. It was the bees that showed me how to move between different flowers—to drink the nectar and gather pollen from both. It is this dance of cross-pollination that can produce a new species of knowledge, a new way of being in the world. After all, there aren’t two worlds, there is just this one good green earth” (p. 47).

Braiding Sweetgrass is just the tonic we need in these troubling and dangerous times. Troubling because of the urgency with which we must reverse the damage humans have done to the Earth (her land, water and air) and all of her lifeforms—human and otherwise. Dangerous because of the imminent threat of extinction to all beings that depend on a healthy planet for survival. Kimmerer fuses indigenous knowledge and wisdom with her scientific knowledge as a botanist. She helps us to understand answers to questions that science has not answered but indigenous peoples have known for millennia—questions about interconnectedness, reciprocity and cooperation among and within species, about the life force inherent in all beings, about alternative forms of communication, about respect and gratitude.

“Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond” (p. 125).

Each chapter takes us on a journey to another plane or dimension that most people are not familiar with. We learn about what other lifeforms can teach humans about survival, and especially about the gifts the Earth has provided.

“We are showered every day with gifts, but they are not meant for us to keep. Their life is in their movement, in the inhale and exhale of our shared breath. Our work and our joy is to pass along the gift and to trust that what we put out into the universe will always come back” (p. 104).

She reminds us that the very way we speak about the natural world denies the vibrancy and “breath of life within” (p. 56), absolves us of “moral responsibility” and “opens the door to exploitation” (p. 57). In contrast, indigenous languages (many of which have already succumbed to forced assimilation) remind us, “in every sentence, of our kinship with all of the animate world” (p. 56).

Kimmerer writes about the sacred connection between humans and plants:

“Plants are… integral to reweaving the connection between land and people. A place becomes a home when it sustains you, when it feeds you in body and spirit” (p. 259).

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (2020) - Isabel Wilkerson

The importance a book has in your life can be directly related to the number of times you quote it, the number of people to whom you recommend it, and the number of zoom interviews with the author you can’t resist. Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste checks all of these for me. It’s a book that gives you the feeling of waking up from the skewing and the lassitude in all those history/social studies classes over decades.

Using metaphors, compelling narrative and deep research, Wilkerson vividly draws the parallels between our racial history and the Nazis’ dehumanization of the Jewish people, and between our racial history and India’s two millennia-long caste system. The parallels aptly apply, though we wish they did not. Carefully building and unfolding her comparisons through exquisite, thorough research and evidence, Wilkerson makes the case for caste.

What is caste? It’s “an artificial construction” in which immutable traits, inherently neutral, are assigned “life-and-death meaning in a hierarchy” that favors the dominant stratum (p. 17). This evocative book brings sadness, anger, deeper understanding and, hopefully, a call to action to form a better society that does not see and exploit differences that are superficial or, indeed, imagined.

The following examples show how Wilkerson uses documented accounts and data. I’ll title these with a phrase used regularly in an early tv detective series

Just the facts:

On the 4th of July, 1910, when black boxer Jack Johnson knocked out James Jeffries, the white boxer dubbed “the Great White Hope,” riots ensued in both the South and North. Eleven riots happened in NYC, where whites set fire to black neighborhoods. Wilkerson writes: “The message was that even in the arena into which the lowest caste had been permitted, they were to know and remain in their place (p. 138).”

Nazi Germany used the US as its model for treatment of the Jewish people and others they deemed undesirable. Roland Freisler, Wilkerson tells us, was a staunch Nazi who researched the US and “its laws of human classification.” Americans had come up with a “political construction of race” to separate blacks from whites. Freisler, the “hanging judge of the Reich,” thought it could work for Germany (p. 85). He advised fellow Nazi leaders: “I am of the opinion that we should proceed with the same primitivity that is used by these American states. Such a procedure would be crude but it would suffice (p. 86).” Strict segregation, endogamy, denial of rights, denial of each black person’s humanity and lynchings—these were key in the American model.

Endogamy laws forbid marriage between blacks and whites. Virginia was the first colony to “outlaw” these marriages in 1691. Our US Supreme Court did not overturn these prohibitions until 1967. However, Wilkerson reminds us that Alabama was the last state to remove its law against intermarriage; the year was 2000. Even then 40% of Alabama’s electorate voted to keep the ban (p. 111).

Wilkerson gives us the data (pp. 314-15) on how our country has changed politically: The last Democratic candidate for President to win a majority of the white vote was Lyndon B. Johnson, winning 59% of white voters in 1964; no Democrat running since then has won a majority of white voters. Among the Democrats: Barack Obama won 43% of the white vote in 2008 and 39% in 2012; Bill Clinton won 39% in 1992 and 44% in 1996; and Jimmy Carter won the largest portion of white voters since LBJ with 48% in 1976. Joe Biden’s election happened after this book was published; in November 2020 he won 41% of white voters.

Between 2014 and 2016, at the end of Obama’s second term, 16 million people were purged from states’ voter registration lists (p. 318, Wilkerson cites this from the Brennan Center for Justice).

Wilkerson calls each of us to “radical empathy.” And she speaks of the importance of language: “You tolerate mosquitoes, you tolerate what you wish would go away. It is no honor to be tolerated. Every spiritual tradition says: love your neighbor as yourself, not tolerate them (p. 386).”

The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science (2023) - Kate Zernike

For fervent, fierce feminists of the 1960s and ‘70s, Kate Zernike’s book is an exceptional review of key life challenges in those decisive decades. It pulls together so many threads that coalesce and show clearly how the line segregating the two predominant genders was one with spikes on the woman-side. These spikes kept women, even women of singular achievement, from advancing. They kept them in a position beneath men, including men of lesser achievement. One example of unequal benefits: Male scientists knew and availed themselves of MIT’s mortgage-lending opportunity; the women scientists did not know, i.e., were not made aware of this opportunity.

For more recent generations, this book is a rich and accessible course on the force for change in those decades. It brings out in relief the imbalances and oppositional pushes against change.

Nancy Hopkins graduated from Radcliffe, the women’s Harvard or “Harvard annex,” in 1964. Zernike describes the context of that time as women wanting career and family, but holding career aspirations more to “executive assistant or part-time position.” Some trends were in a freer direction for women in that year. Just over 12% of women married before graduating college, down from 25% in 1955. And in 1964, British scientist Dorothy Hodgkin became the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.* Marie Curie won the Chemistry Nobel in 1911 and had shared the Nobel in Physics with her husband in 1903. Daughter Irene Curie won in Chemistry in 1935. So Nancy, a very talented scientist, had women models for the highest achievement in science.

Despite this rather promising progress, Zernike’s book is a journey through roadblocks for Nancy and her women colleagues. It is striking and disconcerting that through more than half of this book Nancy does not see the unequal treatment and the denied rewards of top women scientists. Perhaps this is due, in part, to women’s intergenerational, long-held views thwarting self-worth; and perhaps also due to Nancy’s own sense of privilege–she got her PhD at Harvard and worked with James Watson (of Crick and Watson DNA fame). She is stalled in her own reaction to gender discrimination. Even when 20-something Nancy hears 60-something Barbara McClintock (a name synonymous with chromosomes) tell of her own experience with discrimination,** Nancy does not recognize this may also affect her. She believes things will be different for her; the Civil Rights Movement is underway and President Kennedy has passed the Equal Pay Act (1963), prohibiting wage differences based on gender.

This book not only stirred frustration and anger in me for the unequal treatment and mistreatment of women scientists, it incited frustration with Nancy and her excusing of the male behavior that surrounds her. Phil Sharp, whom Nancy worked with and befriended at Cold Spring, makes—with his doctoral student, Sue Berger—a significant discovery of split genes. Phil, however, does not give Berger any credit. Zernike reports that Nancy does talk to Phil about “shorting Sue on credit” (pp. 177-8). However, this does not change Phil. Indeed, he later writes Sue Berger a very weak letter of recommendation. Nancy’s thinking: Phil might believe that “Sue Berger was not so good in science.“ Nancy still does not see that gender has something to do with this unequal treatment.

It might be in the interest of building a strong case and laying out Nancy’s thinking that Zernike stays so long in the book with an unseeing Nancy. Long–through a male colleague locking up the bioimage analyzer that Nancy needs access to for her work. Long–through the forming of women’s groups at MIT and Nancy’s reluctant joining. Long–through her getting high ratings for a required intro Bio course, then being asked to step aside for a male colleague. Long–through the birth of the biotech industry in Cambridge and Nancy accepting Phil Sharp’s statement that “businessmen would not work with women” (p. 189). She accepts being excluded. Long–until Nancy comes up with the idea of effecting change with her male science colleagues and higher-ups by using science, using data.

Zernike describes how Nancy spends weeks of evenings meticulously measuring square footage of the office space of all her colleagues and demonstrating, factually, how men have larger spaces—for office and lab—than women faculty of equal academic rank. She adds gender salary differences to her data. It’s the early 1990s. The situation at MIT is all the more poignant, even startling, given that MIT was in the avant-garde of higher education institutions in admitting women students in 1873.

The book takes us through Nancy-as-reluctant-joiner-of-MIT-faculty-women’s-groups to convener of these groups in her home, and through women faculty across the country looking to MIT and Nancy Hopkins’s work as the model for gender non-discrimination.

On May 31, 2023, the NY Times published an arts piece on a new musical about Rosalind Franklin. Franklin’s “photo 51” of the helix, shown by her colleague to Nancy’s mentor, Jim Watson, was Watson’s ah-ha moment for the double helix structure of DNA. However, Watson gave scant credit to Franklin. The play’s composer/lyricist, Madeline Myers, stated in the article that she didn’t do the play to get audiences “up in arms”; it’s a play about how we use our time, not knowing how much time we have, Myers said. Though time’s constraints on us are worthy of human reflection, a play about Rosalind Franklin had better get the audience up in arms, hopefully 51% of it!

___________________________________

*By 1964 only two other women had won Nobels in the sciences; from the first Nobel award in 1901 through 1922, 60 women and 894 men and 27 organizations were awarded Nobel Prizes.

**McClintock’s plight: Though she and grad student Harriet Creighton were the first to understand the integral role of chromosomal material in the production of sex cells, Barbara was denied a position at Cornell, and only secured one at the University of Missouri through a male faculty member’s grant. End of grant, end of Barbara’s position. Fortunately, through the Carnegie Institution Barbara got a lab at Cold Spring Harbor. In the early 1980s, Barbara, still at Cold Spring and still an underappreciated, so-called “feminine scientist,” won the Nobel.

The Library Book (2018) - Susan Orlean

If you’ve ever visited a library with curiosity and interest, if you’ve ever loved a library, read this book. It can hurt, as it revolves around the story of the 1986 fire that burned nearly all of the Los Angeles Central Library’s collection, delves into the suspected arson and describes the loving, methodical restoration of what books could be repaired.

Orlean evokes so well our feelings about libraries: the mingled scent of new books, old books and humanity; the quiet industry one senses walking in; the gift when leaving with a book or research tucked under an arm. Everyone is of interest to Orlean, from the Library security guard to the Chief Librarian of the City of Los Angeles, and, through her words, we are interested.

The Library Book is something of an American history through libraries—their edifices, their roles, their treasures-on-loan. When the elegant, old Washington Irving Library, which had served its neighbors for over 60 years, is vacated for a modern edifice, Orlean, touring the old structure, writes:

“I have never been in a building as forlorn as this old library, with its bruised beauty, its loneliness…The windows were so dirty only streaky light poured in. The mournfulness felt like a hand pressing on my chest. I have seen plenty of vacant buildings, but this felt more than vacant. This building made the permanence of libraries feel forsaken” (p. 71).

We learn that in 1920, at the start of Prohibition, all library recipe books for booze-making were checked out. In 1942, when World War II was raging and libraries of European countries were burning under Hitler’s assault, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) gave the keynote speech at the American Library Association (ALA) convention. Orlean writes that FDR told America’s librarians: “Books cannot be killed by fire. People die but books never die (p. 202).” And she reminds us that in this war in Poland 80% of all books were destroyed (p. 100). All wars threaten libraries, even ones the US wages. Orlean notes that in the Iraqi War “only thirty percent of books in the Iraqi National Library were spared” (p. 102).

Among the many roles libraries play today, they are often a comfortable chair, a home for their visitors in donated clothing, belongings in a bag beside them and no other safe harbor for afternoons. Many libraries engage social workers to assist in meeting the needs of patrons-without-homes and others. The LA Library hosts Source Day, when community members can get help filling out forms to access an array of needed services, such as food stamps, housing, all in one place—the Library. Concerning innovative roles in our tech-oriented world, in 2014 John Szabo, the City Librarian of the Los Angeles Public Library, established the first accredited, library-based, high school program in the US. Using the library website, adults without a high school diploma can take “Career Online High School” courses free-of-charge and get their diploma. In the Little Tokyo Branch of the LA Library system, Orlean learns that older Japanese men and women will take out children’s books as a way of learning English.

Libraries hold our stories, our personal ones, our author-chronicled ones, our curated ones. The people of Senegal grasp the importance of each person’s story, each “library.” (See quoted text on our homepage.)

And as Orlean states:

“Libraries are physical spaces belonging to a community where we gather to share information. There isn’t anywhere else that fits that description…(Even if we exchange books electronically) libraries will become something more like our town squares, a place that is home when you aren’t at home” (p. 289). Or haven’t got one, I’d add.

We’re reminded to enjoy the special gift that a library is:

“…I wandered alone through the reading room. It was purring with that soothing library noise—not a din, not a racket, just a constant, warm, shapeless sound inhabited peacefully and purposefully by many strangers” (p. 75).

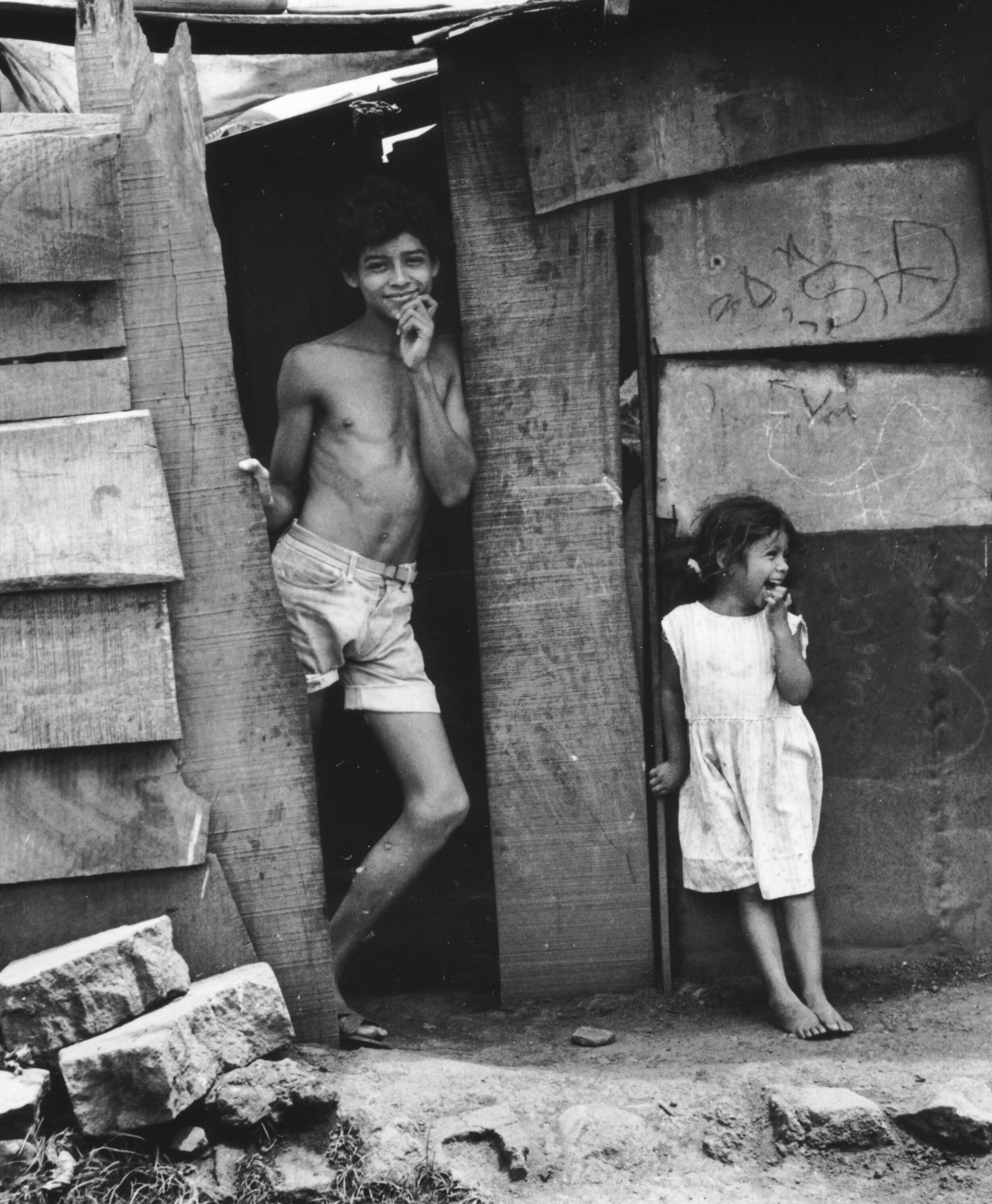

Poverty, By America (2022) - Matthew Desmond

Matthew Desmond, Pulitzer Prize winning author of Evicted, an in-depth examination of homelessness in the United States, offers another brilliant book on the devastating effects of poverty to our citizenry. Desmond argues that poverty is the result of a system in which the interests of many are served by keeping other citizens poor. In his prologue, Desmond asks, “How could there be…such bald scarcity amid such waste and opulence?” (p. 5).

Throughout the book he provides shocking statistics to illustrate the immensity of this problem in the United States, one of the richest democracies in the world, where more than 38 million people–including one in eight children—cannot afford the basic necessities (p .6.) And to address this issue, Desmond summons “[t]hose of us living lives of privilege and plenty [to] examine ourselves… and to become poverty abolitionists, …refusing to live as unwitting enemies of the poor” (pp.7-8).

Throughout the book, Desmond reiterates the consequences of living in poverty; i.e. trauma, violence, fear, shame, addiction, incarceration, bodily harm from living and working near chemical plants, lack of healthcare and, of course, homelessness. The problem of poverty continues to go unsolved, despite the increase in federal relief in medical coverage and assistance. “Part of the answer, … lies in the fact that a fair amount of government aid earmarked for the poor never reaches them” (p.28). States have a great deal of power to determine how to use the money; e.g. for counseling, workshops, rallies, religious events open to the general public.

Single parenting is often cited as a cause for poverty in the US; however, Desmond suggests that this is not the case in Ireland, Italy, or Sweden. “A study of eighteen rich democracies found that single mothers outside the United States were not poorer than the general population” (p. 36). The problem lies in the lack of benefits in the US to single mothers, and to their children, denying them an opportunity to get out of poverty. Additionally, many single mothers and their children suffer isolation due to an anti-family policy inculcated in our incarceration culture. While other countries provide their incarcerated citizens the opportunity to visit family members outside detention centers, the US continues to control who, how and when the incarcerated can interact with their family. Desmond asserts,“In the history of the nation, there has only been one other state sponsored initiative more antifamily than mass incarceration, and that was slavery” (p. 38).

We are living, Demond suggests, in a “servant economy, where an anonymized and underpaid workforce does the bidding of the affluent” (p. 59). We know, he continues, that when wages go up, health improves and alcohol use and child neglect are reduced.

Desmond himself comes from an impoverished background. In a recent interview with Ezra Klein, an American journalist and political analyst for the New York Times, Desmond describes his early childhood as such:

I grew up in a little railroad town in Arizona, Northern Arizona, Winslow, which is an Eagles song. And my dad was a pastor, and we never had a lot of money. Things were tight. Our gas got turned off from time to time. And then we lost our home when I was in college, and I think that experience worked its way inside of me, made me see how poverty diminishes and stresses a family. And then I kind of took that to Milwaukee for my last book and followed families getting evicted and saw a level of poverty that I’ve just never seen before or experienced. I saw grandmas living without heat in the winter, just piling under blankets. I saw kids getting evicted on a routine basis, and I kind of saw a hard bottom layer of deprivation that was just shocking and disturbing. (Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Matthew Desmond - The New York Times)

In the epilogue of the book, Desmond calls on all of us to “direct our obsessions and talents toward abolishing poverty” (p.186). He has hope and asks us to join with groups such as People’s Action and the Rev. William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign to work with groups across faiths, ethnicities and political identities to demand change “from a moral perspective.” For Desmond:

… poverty is not just a line. It’s not just an income level. Poverty is often pain and sickness. It’s living in degraded housing. It’s the fear of eviction. It is eviction and the homelessness. It’s getting roughed up by the police sometimes. It’s schools that are just bursting at the seams. It’s neighborhoods where everyone around you is also struggling. It’s death, death come early, death come often. So for me, poverty isn’t a line. It’s this tight knot of agonies, and humiliations, and social problems, and this is experienced by millions of us in the richest country in the history of the world. (Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Matthew Desmond - The New York Times)

The Trayvon Generation (2022) - Elizabeth Alexander

“Racial ideologies are insidious. They instruct in intricate ambient teaching systems. The country is their classroom and everyone is in school whether they choose to be or not” (p. 4).

“Here is the thorny truth: while many sectors of society are now more integrated, violence and fear are unabated” (p. 5).

Thusly, Elizabeth Alexander—wordsmith extraordinaire, poet, mother, educator—writes in chapter one of The Trayvon Generation, a very personal but also philosophical work that integrates history, art, poetry and sociology. From the outset, Alexander wants us all to understand that everyone of us is affected by the culture in which we are immersed. And our culture is one in which racism and white supremacy, hatred and violence are deeply embedded. She demonstrates some of the ways in which our institutions, especially our educational institutions promote the dominant culture and perpetuate myths about Black and Brown people at the same time that they either relegate them to an inferior status or render them completely invisible.

She interrogates the impact that living in this culture has on us, and especially on Black and Brown young people who experience and/or witness first-hand the hatred and brutality exacted against others like them, day after day. It is here that she identifies the defining characteristic of what she terms “the Trayvon Generation” (one that will necessarily, impact all generations that follow). Today, young people have their phones as extensions of their own bodies and can replay over and over, the videos of violence inflicted upon Black and Brown people. So Alexander asks, what does that do to a young person’s sense of self, to their dignity and humanity? How does one heal from that constant trauma?

Alexander levels difficult questions at all of us, whether we are parents of Black and/or Brown youngsters or not. How do we collectively and individually raise our young people to have self-respect and respect for other living beings in a society and culture that have neither? How do we raise whole human beings who have true hearts and spirit? How do we keep them safe? These are the constant burdens that weigh heavily on the parents of Black and Brown kids. Alexander writes: “If Black children belong to us—and we need not be mothers, or fathers, or even Black for Black children to belong to us—a part of us is always vigilant, and always exhausted” (p. 120).

Alexander describes the conundrum she faces as the mother of Black children:

“If I listen to their fears, will I comfort them? If I share my fears will I frighten them? Will racism and fear disable them? Will dealing with race fill their minds with stones and block them from thinking of a million other things? (p. 71)…I want my children—all of them—to thrive, to be fully alive. How do we measure what that means?…How to access the sources of strength that transcend this American nightmare of racism and racist violence?” (p. 73).

This leads us to her final theme which has to do with the idea that culture is not static, that we can perpetuate it as well as create it. Alexander infuses her book with art and the creative response by Black and Brown artists—poets, musicians, painters, etc.—to the trauma of racism. Somehow these (and other) artists have transcended the horrors to create works that are both evocative and meditative. Their work represents an avenue for pursuing solutions to the problems confronting us. As Alexander writes, “Art and history are indelible. They outlive flesh. They offer us a compass or a lantern with which to move through the wilderness and allow us to imagine something different and better” (p. 124).

(Note: See our poetry section for a video of Elizabeth Alexander performing her poem, “Praise Song for the Day" at President Barack Obama’s Presidential Inauguration on January 20, 2009.)

UNTHINKABLE: Trauma, Truth, and the Trials of American Democracy (2022) - Jamie Raskin

The epigram attributed to Albert Camus at the beginning of Jamie Raskin’s book, Unthinkable–“I realized, through it all, that in the midst of winter, there was, within me, an invincible summer”—explains a great deal about Raskin—the man, the father and husband, the Constitutional lawyer and professor, one of Maryland’s eight representatives to the U.S. House of Representatives and the lead manager in the second impeachment trial against former President Donald Trump. Raskin, at once extraordinary and down-to-earth, brilliant yet quick to acknowledge the astute contributions and brilliance of others, strategic and self-questioning, seems always to believe in the humanity and decency of others. “Optimistic” doesn’t quite get it; rather, Raskin expresses the belief that people will uphold the Truth, and will act not only in accordance with the facts, but ethically and morally. As it becomes clear throughout the book, “within” Raskin is a commitment or tenaciousness to get at the Truth, but at the same time, a sincerely felt warmth and compassion for others.

Early on, we learn that on December 31, 2020, Raskin’s 25-year-old son, Tommy, a supremely intelligent and compassionate young man who long struggled with depression, committed suicide.

On January 06, 2021, after a rally led by Trump himself, a violent and angry mob of approximately 2,000 or more Trump supporters, brandishing as weapons, flagpoles, baseball bats, and chemical sprays, stormed and ransacked the Capitol to subvert the official certification of the Electoral College vote which Joe Biden had won 306-232. (Biden also won the popular vote with over 81 million votes to Trump’s 74 million.)

At the urging of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, Raskin agreed to take on the responsibility of leading the impeachment trial against Trump for having incited the Insurrection and for doing nothing for hours on end to quell the mob, which left several dead, about 140 police officers wounded, and several million dollars worth of damage.

In Unthinkable, Raskin writes about his family’s trauma after losing Tommy, and weaves that into the nation’s trauma of January 06 and its aftermath. He takes us behind the scenes inside the Capitol on that day. He also takes us through the preparations for the impeachment trial, the massive amount of evidence in video footage, emails, etc., that the managers collected, and what they discovered along the way. He explains Trump’s strategy to maintain power—claiming fraud and discounting the election results well before the election even took place, filing more than 63 unsuccessful lawsuits claiming election fraud in various states after election day, pressuring Republican election officials and governors in several states where Biden won, to declare their election results invalid, trying to convince Mike Pence to discount the results of the Electoral College in the certification process on January 06, and, finally, inciting a riot at the Capitol to prevent the certification of Biden as President-elect.

Raskin teaches us a lot about the Constitution, for example, the “foreign emoluments clause” (Article I, section 9, clause 8 of the Constitution). It “prohibits any person holding a government office from accepting any present, emolument, office, or title from any "King, Prince, or foreign State," without congressional consent,” and the domestic emoluments clause (Article II, Section 1, Paragraph 7 of the Constitution) which “prohibits the president from receiving any personal benefit from the government of the United States or individual states.” We learn that while he was President, Trump violated these laws many times in a variety of ways, by refusing “to divest himself of his corporate holdings or even to stop doing business while in the White House” (p. 199), thus profiting from having foreign dignitaries reside or use office space at the Trump Hotel, and at other Trump-owned buildings, golf clubs and enterprises.

We learn about the flaws of the Electoral College–how it favors the wealthy elites and the southern and less populated states, and that it was established with a deep distrust of ordinary people. We learn that if a candidate for president does not receive 270 Electoral College votes for whatever reason (for example, if there are three or more candidates who split the total vote, or if votes or slates of electors are invalidated, etc.), then the election outcome is determined by the House of Representatives in a “constituent election” (a “one state-one vote” election rather than in a “one person-one vote” election). Thus, it would appear that Trump’s strategy to maintain the Presidency was to disqualify the votes from several of the states that Biden had won so as, to decrease the latter’s total electoral vote count from 306 to less than 270, thus throwing the election into the House for a constituent election that Trump could have won.

Unthinkable is critical reading. It is both a “page-turner” and devastating; it is definitely hard to take in all at once. Raskin’s commitment to the Truth, to the Constitution, to “a more perfect union,” and to a truly democratic society—one we have yet to achieve—is awe-inspiring. His love for his family, this Nation, and humanity serves as a model for us all.

Web design and administration by ericagailpolakoff. Unless otherwise noted, all images are original photographs ©2022 by ericagailpolakoff.

For polakoff’s photo website see: ericagailpolakoffphoto.net